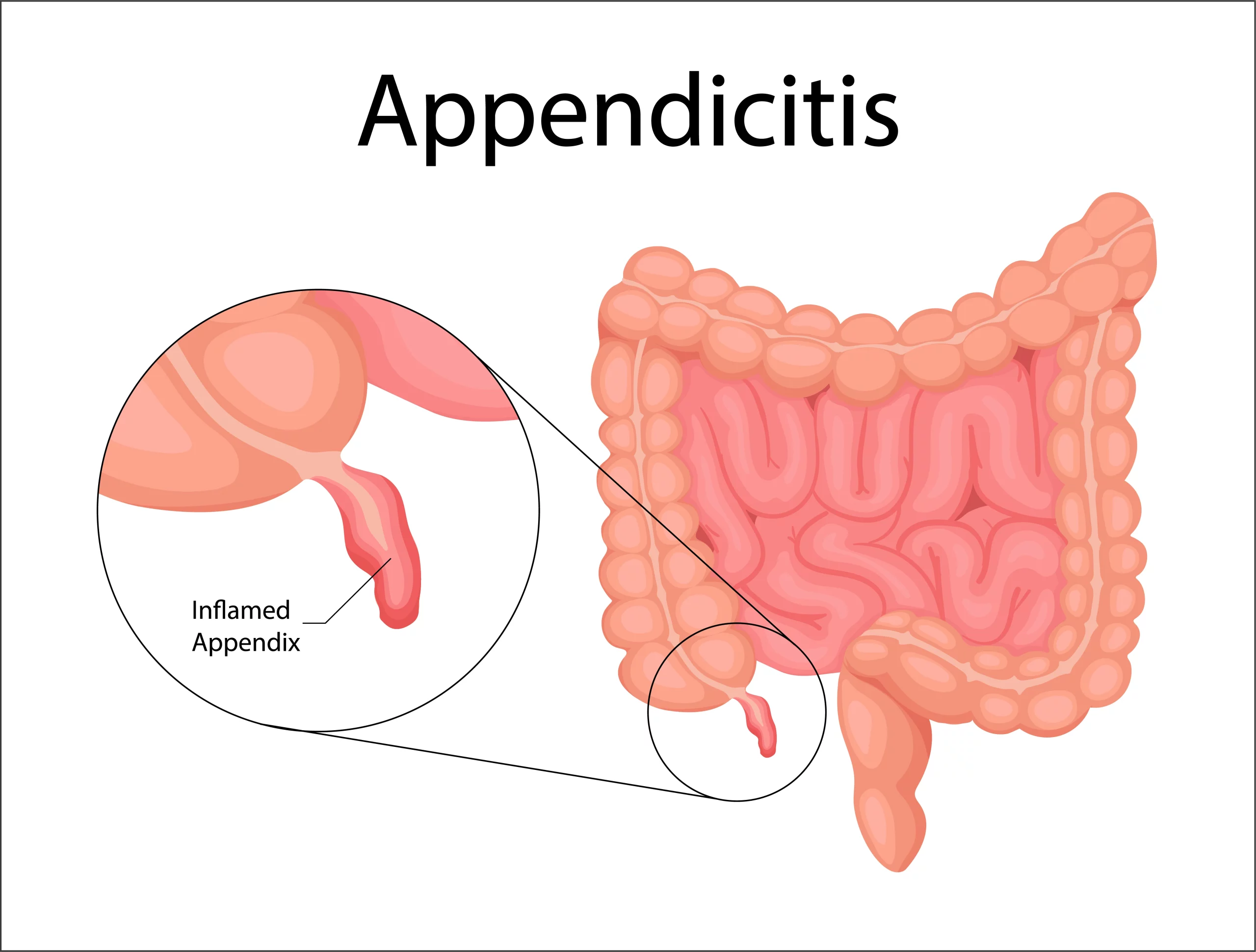

Appendicitis refers to the inflammation of the appendix, a finger-shaped, small organ situated in the lower right side of the abdomen, connecting to the large intestine (colon).

Inflammation causes the appendix to swell and fill with a thick, infectious fluid known as pus. If left untreated, an appendix inflammation can damage, leading to the release of pus into the abdominal cavity, causing infection.

This article endeavors to delve into the various factors that initiate inflammation of the appendix. Furthermore, it will elucidate the symptoms, diagnosis, and available treatment options for individuals affected by appendicitis.

Causes of Appendicitis

The most common cause of appendicitis is a blockage in the appendiceal lumen which is the internal area that flows into the large intestine. Various factors or scenarios can contribute to this blockage:

Appendicitis can be triggered by various factors, including the presence of a fecalith, which is a hardened pile of stool. Another potential cause is lymphoid hyperplasia, characterized by the expansion of lymphoid tissue within the appendix. Infections within the digestive tract, whether viral, fungal, bacterial, or parasitic, can also contribute to the development of appendicitis.

Moreover, noncancerous or cancerous growths within either the appendix or the large intestine may lead to inflammation and subsequent complications. Appendicoliths, defined as firm, tightly formed stool and minerals in the appendix, represent another factor that can block the normal function of the appendix and contribute to appendicitis.

Pain to the abdomen is identified as a potential cause, emphasizing the importance of considering physical injury as a factor in the onset of appendicitis. Additionally, although rare, the ingestion of seeds from fruits such as melons, oranges, and grapes, or rare objects, can also play a role in the development of appendicitis.

Understanding these diverse factors is essential in identifying the root causes of appendicitis and guiding appropriate medical interventions. Each of these contributors underscores the complexity of this condition and the need for a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment.

Consequences of Blockage

When the appendiceal lumen is blocked, the appendix undergoes swelling, becomes sore, and accumulates pus. The subsequent swelling and pressure buildup disrupt the blood supply, leading to necrosis (tissue death).

Rupture and Complications

The disruption of blood supply increases the risk of bursting or rupture of the appendix. In case of brust, leaked pus can create an abscess all over the appendix or spread deeper into the abdomen, causing a severe and dangerous infection known as peritonitis.

Factors Influencing Rupture

Type of Blockage

Certain factors, such as the kind of blockage, may influence the likelihood of appendix rupture. Research suggests that appendicoliths are more frequently associated with appendix burst compared to other results of blockages, like fecaliths.

Common Risk Factors

People with the following characteristics are more prone to appendix rupture:

1. Age over 60 years.

2. Fever higher than 99.1 degrees F.

3. The manifestation of guarding observed during a physical examination (tensing of stomach muscles in anticipation of pressure).

4. Elevated white blood cell count.

5. Prolonged pain lasting more than 24 hours.

Understanding these causes and risk factors is crucial for identifying and managing appendicitis promptly.

Is appendicitis consistently considered a medical emergency?

Appendicitis is unequivocally considered a medical emergency, and swift intervention is imperative. Without prompt treatment, an appendix inflammation poses the risk of burst, leading to severe or potentially deadly complications such as abscess formation or peritonitis.

Symptoms Preceding Appendicitis Rupture

The hallmark symptom of appendicitis is abdominal pain, a pervasive indicator present in nearly all cases. Typically initiating near the naval, the pain progressively migrates to the abdomen at the lower right side. Initially vague and crampy, the pain intensifies over a span of 12 to 24 hours, becoming sharper and more severe.

The manifestation of pain can vary based on the anatomical location of the appendix and other factors, including age. Pregnant individuals experiencing appendicitis may feel pain in the upper right side of the abdomen rather than the lower right side. Similarly, in older individuals, the abdominal pain may stay mild and initiate in the lower right side instead of all over the naval.

In conjunction with abdominal pain, appendicitis may present with additional symptoms:

1. vomiting (typically following the onset of abdominal pain)

2. Lack of appetite

3. Diarrhea or Constipation

4. General feelings of unwellness

5. Low fever

Symptoms Following Appendicitis Rupture

In the event of an appendix rupture and the development of complications such as peritonitis, the ensuing symptoms and signs become more pronounced and severe:

1. Critical abdominal pain

2. High-grade fever

3. Uncontrollable shaking or shivering (rigors)

4. Hypotension

5 Rapid heart rate

Recognizing these symptoms is crucial in determining the urgency of medical attention, as the severity of appendicitis can escalate rapidly, particularly following a rupture. Early diagnosis and intervention significantly impact the prognosis and reduce the chance of life-threatening complications.

Diagnosing Appendicitis

Diagnosing appendicitis involves a comprehensive assessment by doctors, employing risk stratification by considering various factors. This evaluation encompasses the patient’s symptoms, findings from a physical examination, and results from blood and imaging tests. Despite the diagnostic process, appendicitis can be challenging to identify, particularly when it presents with atypical signs or symptoms, or when imaging results lack clarity, potentially leading to misdiagnoses such as acute gastroenteritis.

Physical Exam

During the physical testing, doctors conduct a thorough assessment, gently applying pressure to the abdomen. Pain in the lower right side of the stomach is a hallmark sign of appendicitis. The presence of stiffness in stomach muscles and guarding can also be noted. A digital rectal examination, involving the insertion of a gloved, finger which is lubricated into the rectum, is performed. Right-sided rectal tenderness supports the diagnosis of appendicitis. Additionally, a pelvic examination may be administered to rule out gynecologic conditions mimicking appendicitis.

Blood Tests

Blood tests, including a white blood cell count and C-reactive protein (CRP) level, are commonly conducted when appendicitis is guessed. An increased white blood cell count indicates infection, while an increased CRP recommends inflammation. In some cases, a urinalysis may be performed, potentially leading to misdiagnoses, as white blood cells in the urine can be observed in chronic appendicitis, mimicking symptoms of a urinary tract infection.

Imaging Tests

Imaging plays a crucial role in confirming appendicitis and assessing its severity. While highly sensitive and specific, imaging tests may still miss cases. For adult appendicitis, the preferred imaging test is an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, a specialized X-ray producing a three-dimensional image. In the case of children or pregnant individuals, an abdominal ultrasound is the preferred imaging study, offering visualization through sound waves without radiation exposure. These imaging modalities aid in confirming the diagnosis, determining the presence of a ruptured appendix, and excluding alternative diagnoses.

Most Common Treatments for Appendicitis

The primary and standard treatment for appendicitis is appendectomy, a surgical procedure involving the removal of the appendix. Typically conducted by a surgeon under general anesthesia, appendectomy can be performed through two main methods:

Open Surgery

In open surgery, a scalpel is used to make a large cut down and to the right of the naval. The appendix is then removed through this sizable incision. Open surgery is suggested when the appendix is highly inflamed or has burst, and it may be the preferred approach in the presence of scar tissue from previous abdominal surgery.

Laparoscopic Surgery

Laparoscopic surgery involves making numerous small cuts in the abdomen. Long and thin instruments are sent through these incisions to remove the appendix. This method offers advantages such as a shorter recovery time, reduced pain, and minimal scarring. However, not everyone is a suitable candidate for laparoscopic surgery.

Surgery vs. Antibiotics

In some cases where the appendix has not burst, and there is no proof of peritonitis or abscess formation, antibiotics may serve as an alternative treatment to surgery. Antibiotics are administered intravenously for some days, continued by more than a wee\k of oral antibiotics. This approach is considered particularly when surgery poses risks or is not feasible.

Recurrence After Antibiotics

While antibiotic treatment provides the advantage of a faster recovery, a notable drawback is the potential for appendicitis recurrence. According to one study, nearly 40% of individuals who have taken antibiotics for appendicitis experienced recurrent appendicitis within 5 years. This underscores the importance of considering both the benefits and risks when determining the most suitable treatment approach for appendicitis

Post-Appendectomy Healing and Rehabilitation

The recuperation period following an appendectomy typically proceeds smoothly and expeditiously, contingent upon whether the procedure was performed through an open or laparoscopic approach.

For Laparoscopic Appendectomy

If you go through a laparoscopic appendectomy, your hospital stay may extend to just one night, or in some cases, you might even be discharged on the day as the proedure. This minimally invasive technique often facilitates a quicker recovery.

For Open Appendectomy

In contrast, an open surgery may necessitate a longer hospital stay, extending up to three days. The duration of the hospital stay is influenced by factors such as the extent of the surgery and the individual’s response to the procedure.

Postoperative Pain and Care

Ache in the abdominal region and around the cut site(s) is a common postoperative experience. Following discharge from the hospital, adherence to specific postoperative instructions is crucial. These instructions encompass:

Incision Site Care

Keeping the abdominal cut site(s) dry and clean to avoid infection.

Pain Management

Taking prescribed pain medication as directed to alleviate discomfort during the recovery phase.

Resuming Activities

Adhering to guidelines regarding the timing of resuming various activities, including driving, working, and engaging in heavy lifting. The recovery timeline may vary based on individual healing rates and the type of surgery performed.

Follow-Up with Surgeon

Scheduling and attending follow-up appointments with the surgeon to monitor the healing process, address any concerns, and ensure a successful recovery.

Navigating these postoperative instructions diligently is instrumental in fostering a smooth recovery journey after an appendectomy, promoting optimal healing and a swift return to regular activities.

Conclusion

In conclusion, appendicitis is a medical emergency characterized by the inflammation of the appendix, demanding prompt attention to mitigate the risk of severe complications such as rupture, abscess formation, or peritonitis. Delving into the intricacies of appendicitis reveals diverse causative factors, ranging from blockages within the appendix lumen to infections, growths, and trauma. Recognizing the symptoms, especially abdominal pain, nausea, and fever, plays a pivotal role in early diagnosis.

The diagnostic process involves a meticulous examination by healthcare providers, assessing symptoms, conducting physical examinations, and utilizing blood and imaging tests. This comprehensive evaluation aids in determining the appropriate course of treatment, with appendectomy, the surgical removal of the appendix, standing as the standard and most common approach. The choice between open and laparoscopic surgery depends on factors such as the severity of inflammation and the patient’s overall condition.

While appendectomy remains the primary treatment, the emergence of antibiotic therapy as an alternative for select cases highlights the evolving landscape of appendicitis management. Antibiotics may be considered when the appendix is not ruptured, and there is no evidence of abscess or peritonitis, providing a viable option for those who may not be suitable candidates for surgery.

Post-surgery, the recovery process varies based on the surgical technique employed. Laparoscopic procedures often result in a quicker recovery, allowing for same-day discharge in some cases, while open surgeries may necessitate a more extended hospital stay. Postoperative care involves diligent adherence to instructions regarding incision site care, pain management, resumption of activities, and scheduled follow-up appointments with the surgeon.

In navigating the complexities of appendicitis, a comprehensive understanding of its causes, diagnostic procedures, treatment options, and recovery processes is paramount. This knowledge empowers individuals and healthcare providers alike to make informed decisions, ensuring timely intervention and optimal outcomes for those affected by this common yet potentially serious condition.