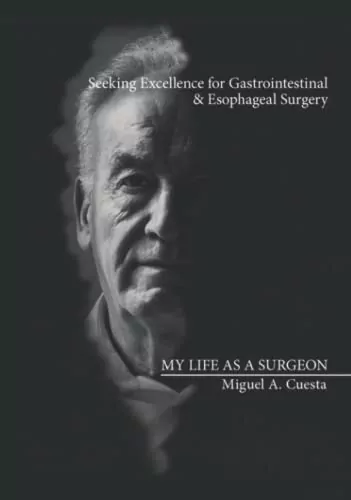

Description

When Index of Sciences Ltd asked me to write my professional biography, I first thought the idea was a little arrogant and exaggerated. Reflection on that made me realize that it did not need to be about me as much as about the fascinating life I had as a surgeon and the exhilaration of practicing with others with who I was privileged to be involved. I thought, ‘Maybe I can shed some light on the standards of excellence involved in being a surgeon.’

Currently, I am an Emeritus Professor in Gastrointestinal Surgery, and as an academic surgeon working at the VUmc in Amsterdam, I have been involved my whole working life doing three things: treating surgical patients, implementing treatments for digestive diseases in minimally invasive surgery, and looking for evidence that Minimally Invasive Gastrointestinal Surgery is superior or at least not inferior to the conventional open approaches. Now, these tasks belong to the position of being a surgeon, so what could be relevant for others beyond just telling what simply being a surgeon is? So my first question was: ‘What can I share with those people who are not involved in medicine or surgery so that they could consider my biography to be interesting and relevant? My first feeling about this was negative because writing implies being able to convey knowledge in a fine and instructive way.

Luckily, the redaction assistant Mr. Art Culton explained to me that writing a surgeon’s biography would be very interesting for many people, not only for other surgeons and I could be assured that I would be aided with the writing. That helped me to decide to do the biography and I became convinced that focussing on some challenging aspects of my professional life would sufficiently interest a broad public and add to the luster of the profession of the surgeon. So, I have tried to portray aspects of my professional life as a surgeon in 20 chapters; starting from the beginning of my career to after my retirement in 2014. I explain in a sequential way how the life of a surgeon developed in a specific direction to finalize, as in my case, as an academic surgeon.

I can distinguish three periods in my life as a surgeon: first, there is the period of formation that commenced in the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad de Navarra in Pamplona, followed up by my time in the Department of Surgery in the Francisco Franco Hospital in Madrid, and finalizing during the residency period of six years at the VUmc in Amsterdam. I consider myself very lucky that I could learn medicine and surgery at these three institutions with such great programs, their outstanding teachers, all within a context full of discipline. The second period was my work as a general surgeon in Toledo, where I learned to operate and developed the social aptitudes to communicate with different kinds of people in different situations. The third period started with my ambition to become an academic surgeon. Initially, I attempted to get a training place at one of the Academic Hospitals in Spain, but without success due to bureaucracy and the interference by the Trade Unions.

Hence, I decided for the second time to move to Amsterdam to the VUmc, where I was accepted for a stage of one year for oncological surgery. The opportunity the academic institution in the Netherlands offered me for realizing my dreams was a contrast with the Spanish way of selecting candidates, those were frequently chosen before the exams, making these attempts and examens worthless, losing time. This situation is not changed currently, many Spanish surgeons, after years abroad, wishing to go back to Spain for work, are systematically hindered by strange rules of points. In Amsterdam, I was able to develop my dreams and creativity as a surgeon; I felt ‘the sky is the limit.’ I experienced Dutch society as an ideal place to learn and work, so down-to-earth and straightforward and quite meritorious: if you work hard and creatively you will be honored. I met there, not only at the VU but in the national Dutch Surgical society many people with the same interest in developing Minimally Invasive Surgery.

That led us to create a compact group to develop new procedures and at the same time cooperatively proving by Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) the evidence that Minimally Invasive Surgery was better than conventional surgery. It was a beautiful time, not only developing this MIS but also the whole field of surgery was changing in a more participative and organized way, by ongoing creation of specialisms, by changing the concept of teaching residents, instituting centralization policy, and by introducing an obligatory registration system. All this was done with the overarching goal to seek the highest quality in surgery.

It is my privilege to share these challenges and core concepts in the 20 chapters. In some developments, I could perform as a principal actor while at other times only as a secondary actor and finally in other happenings only as a spectator. But as I hope to convey, certainly as a spectator filled with enthusiasm and even now yet clapping for the new principal actors with admiration, recognition, and positive criticism. What I also intend to portray is that there have been so many developments in the last thirty years, which is a whole working life, wonderfully filled with acquaintances, national and international friendships, anecdotes, meetings, and congresses, teaching people, all in combination with our aim of the best care for the patients. All this may show that the future of GI surgery is continually introducing new technologies, such as the robot, artificial intelligence, new instruments, but always keeping in mind that the indication to operate remains the cornerstone of surgery.

From reading this autobiography, lay people can learn to understand that even after a surgeon comes up with a brilliant idea, it still takes much time and effort, for even the best ideas cannot be implemented immediately in daily practice. A long process of generating a new practice follows, even when guided by the principles of the IDEAL frame of development with at the end an RCT comparing the new with the old procedure to adopt the new procedure only in the case that this is equal or superior to the old procedure. The next step after an RCT is dealing with how to implement the new treatment in a surgical community. Because this implementation implies a long process of learning, I believe this should be organized and controlled by the surgical societies, not by the governments.

Hopefully, the interesting take-home message of this biography will be that everything from the EUREKA moment for an innovative technique until its implementation in daily practice can only be done by engaging in a careful process of professionalization. What I hope to share in this rendition of my life as a surgeon is that the core of such professionalization always must be our patients who must receive total respect and care when it comes to establishing an innovation. Demonstrating this standard of excellence is the goal of my biography.

I wish to express my deeply felt gratitude to all patients and colleagues that I have treated or met during my professional life and to the Index of Sciences publishers for involving me in this enterprise.